What do you get when you cross Amtrak, civil rights, and a library?

They were the internet before the internet. That’s how Kizzy Downie, a community service director in St. Paul, describes the African-American railroad porters hired just after the Civil War. During their cross-country travels, porters “would meet in rooms and swap books, pass around magazines and newspapers,” says Downie. “There was a shared experience, and that was the inspiration for the Reading Room.”

Downie is describing a gathering space in the newly redeveloped mixed-use Brownstone building at University and Victoria avenues in the Rondo neighborhood of St. Paul. The $14 million affordable housing project, created by the nonprofit Model Cities, lies adjacent to a Green Line LRT stop; restaurant and retail business will fill spaces on the ground floor. The Reading Room, which opened to the public in late July, comes to life through art, artifacts, and books commemorating the struggle for social and economic justice.

The Pullman porters represent a special focus of the collection. The porters took their name from George Pullman, the Chicago industrialist who founded the first sleeper train car company. Pullman hired African-American men at low wages to serve wealthier white travelers en route.

“This arrangement reproduced master-slave relations in a post-slave time,” says Yuichiro Onishi, an associate professor of African-American studies at the University of Minnesota. “They weren’t allowed to use their own names.” Instead, they “were all called George.” Yet the paid work, Onishi adds, enabled “these workers to achieve some mobility.” By the end of the 19th century, the Pullman company was the largest single employer of African-American men in the United States. St. Paul’s black community counted many railroad workers. Civil rights leader Frank Boyd, for example, worked as a Pullman porter before he organized one of the country’s most influential African-American labor unions.

“We wanted to honor them,” Downie says. “They were part of the labor movement that helped everybody in society.”

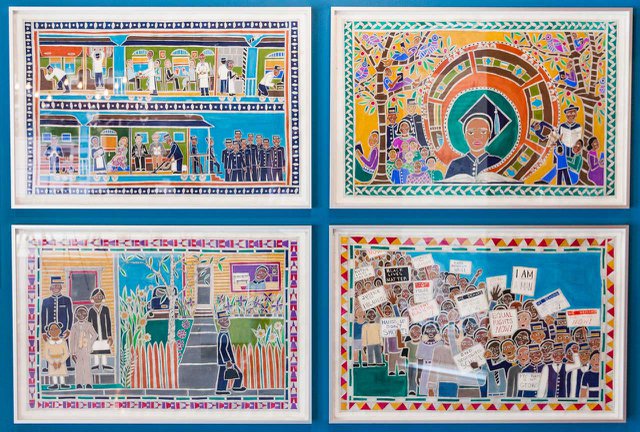

The Model Cities team hosted a series of ideation sessions with local architects, artists, and Minnesota Historical Society reps to collect input about the room and renderings for the space. Inside the Reading Room, a wall-sized, sepia-toned print shows six Pullman porters from the 1920s. Custom bookshelves, made from iron and reclaimed wood, mimic train tracks. The collection—curated by Onishi and Moon Palace Books, in Minneapolis—includes fiction and nonfiction: young adult books like Angie Thomas’s The Hate U Give, and selected works of W.E.B. Du Bois. Model Cities also tapped seven local artists to reflect on the legacy of the Pullman porters. Lela Pierce, for instance, contributed My Name Is Not George, a four-piece pen-and-paint work. Pierce was inspired by her late grandfather, Eulis C. Pierce Sr., a Pullman porter during the early 1940s, who also lived in Rondo.

A 2016 photograph by Caroline Yang pulls these themes into the present. The striking image depicts a blue line of uniformed police officers holding batons, in front of the Governor’s Mansion in St. Paul. Police brutality protesters stand facing them. Yang writes about the photograph, “My goal is to look beyond the ideology and tactics, and reveal the humanity that connects us all.” Wherever the civil rights journey is heading, Yang’s print suggests, we still have a few stops to go.

(Original Link: http://mspmag.com/arts-and-culture/the-reading-room-honors-st-pauls-civil-rights-journey/)